Graveyard Musings goes to Belgium

- Claire Sandys

- Jun 6, 2023

- 13 min read

My Why podcast version of this blog available here.

You might remember a little while ago I did a few episodes called Graveyard Musings, where I wandered around our local graveyard musing about what I saw. Well, I'm back, but this is an extended international edition because it not only contains my musings from the world’s largest cemetery for Commonwealth soldiers, it also gives you a bit of the history of why it’s there and the other ways these soldiers are being remembered.

Last Christmas (2022), Chris and I decided to go away for Christmas, for the first time since we got married 18 years ago, and we went to Belgium. From our house in England that’s a 3-4 hour drive, a 30 minute transfer under the English Channel and then just over an hour drive through France and into Belgium. Yes folks from giant countries, that’s how we roll in Europe - 3 countries in just under 3 hours.

Boarding the Eurostar:

I hadn’t been to Belgium before but Chris had been a couple of times over the last few years (mostly for the craft beer scene), and he’d return every time saying - ‘I must take you to see the war history’. Now, I knew it had to be something special for him to say that because, well, war history isn’t something I’m known for seeking after. However, he was right. It was fascinating, humbling and inspiring all at once.

In fact it was probably the one form of loss I was faced with where I thought I could potentially use the words ‘I can’t imagine’ in the right context. I know a lot of people we’ve spoken to on the podcast don’t like hearing those words when they’re grieving, because it puts a wall between them and the person saying it, and I get that. But in the context of losing hundreds of thousands of people, the deaths of this many men, in one place, at one time, for one cause, well, it was hard to imagine how people got through it. I could imagine the impact it would have, but not how people coped.

While I was there I recorded a few bits of audio as I walked around the war cemetery, and now, yes, 6 months later, I’m finally getting them sorted into an episode for you. It’s an international version of my Graveyard Musings (to listen click here).

First, I’ll give you a bit of info on the area we stayed in, Ypres (silent s, took me a long while to work out how to pronounce it). Chris chose here for the history (and the beer! Although it didn’t hurt that they have the most amazing marzipan shop in Bruges nearby too).

In this area during the First World War there were a few battles that took place in the Ypres Salient, including the First Battle of Ypres (1914), the Second Battle of Ypres (1915) and the Third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele (1917). The Battle of Passchendaele, by far the worst for casualties and deaths, was for control of the south and east of the Belgian city of Ypres in West Flanders. Even if you’re not into history you may have heard of - Flanders Fields - a common name for the World War I battlefields in Belgian between West and East Flanders. The fighting was between the German, and the Allied armies (which included Belgian, France, Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand).

In an article called ‘Passchendaele Inside the First World War’s Infamous Slaughter in the Mud’, by Darrell Duthie, in 2017 he wrote about what happened there during the First World War and said this:

One of the bloodiest and most controversial battles in World War One, the Passchendaele Offensive, came to an end on Nov. 10, 1917. It had been a clash of titans, a wearying three-and-a-half-month ordeal in the mud during which more than a half-million men on both sides were killed or wounded. Darrell Duthie

Basically, the British were planning to break through the semi-circle of German trenches on the high ground overlooking Ypres - which was where we were staying. Once the British got through they were going to make for the U-Boat bases on the coast to draw Germans away from the French army that was struggling in the wake of another battle.

But heavy rain (the wettest August for 30 years) and massive artillery bombardments turned the ground at Passchendaele into a bog that they had to battle through. Finally the ruins of the village of Passchendaele were liberated and the German trenches fell.

The appalling casualties, the mud and the overall futility of the offensive have made Passchendaele an emblem of the mind-boggling waste of the First World War. Darrell Duthie

Apparently in June 1917 British, Canadian and Australian tunnellers burrowed underneath the German defences in the Ypres Salient and planted 21 massive explosive mines. When they were detonated in rapid succession the rumble could be heard as far away as London! Two of the mines failed to explode. One was detonated by lightning in 1955, killing a cow, and another was discovered under a Belgium farm but even now it’s too dangerous to dismantle.

Casualties of the entire battle are disputed and debated but the Imperial War Museums website says…

The Allies suffered over 250,000 casualties - soldiers killed, wounded or missing - during the Third Battle of Ypres. Casualties among German forces were also in the region of 200,000. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemorates over 76,000 soldiers who died during the Third Battle of Ypres. More than half have no known grave. Imperial War Museums website

This was across just 5 miles (8 kilometres) of ground taken. Which works out that a man was killed or wounded for every 2.5cm of ground gained.

Over a hundred years after the battle, the countryside still regularly throws up reminders of history - in fact an entire unit of the Belgian military has the job of disposing of this ‘iron harvest’ - unexploded shells from another century. Millions and millions of shells were fired. And as you drive around the area now you will see concrete posts and telegraph poles with holes in, if farmers find unexploded shells on their land they place them there for collection. We saw many when we were there.

It’s said that more than 100 tons of unexploded items are still discovered every year.

One of the history buffs we bumped into made the mind-blowing comment that theoretically a shell could have been fired in the First World War and kill someone 3-4 generations down the line ahead of them today.

But what’s so amazing about this area, isn’t only the extent of the awful loss suffered, but it’s how it’s remembered.

Not only are there more than 100 small cemeteries within a 16 mile radius of Ypres filled with the dead from Passchendaele, but there were also many many men that were lost in the muddy wasteland of Flanders Fields and never found, 42,000 bodies.

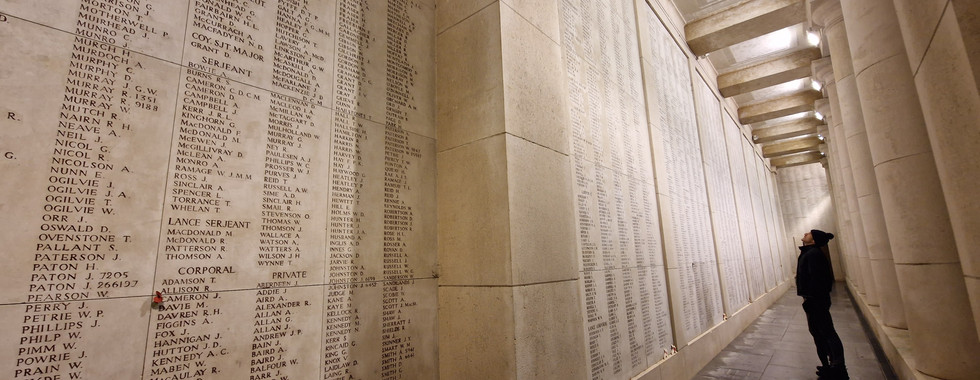

So their names have been commemorated somewhere very special. On the Menin Gate in Ypres. A huge war memorial, built on this site because of the hundreds of thousands of men who passed through it on their way to the battlefields, many who never returned. It’s a vast, impressive archway that the traffic passes through daily, and it commemorates casualties from the forces of Australia, Canada, India, South Africa and United Kingdom who died in the Salient. To this day, sometimes the remains of missing soldiers are found in the countryside around Ypres, often during building or road works. They then receive a proper burial in one of the war cemeteries, or if identified, their name is removed from the Menin Gate.

On the Menin Gate are inscriptions proposed by Rudyard Kipling:

To the greater glory of God - Here are recorded names of officers and men who fell in Ypres Salient, but to whom the fortune of war denied the known and honoured burial given to their comrades in death. They shall receive a crown of glory that fadeth not away.

And every day the 54,896 missing soldiers who died in the First World War and have no known grave are remembered in a very special way, as it states on the website (lastpost.be):

The daily act of remembrance - The Salute to the Fallen The Last Post, the traditional final salute to the fallen, is played by the buglers of the Last Post Association in honour of the memory of the soldiers of the former British Empire and its allies, who died in the Ypres Salient during the First World War (1914-1918). It is the intention of the Last Post Association to maintain this daily act of homage in perpetuity. Every evening at exactly 8 o’clock, the police halts the traffic passing under the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing in the Belgian city of Ieper to allow the buglers to play their simple but moving tribute. Everyone can attend this Last Post Ceremony free of charge, without the need for prior reservation, unless you wish to actively participate.

And that’s what they’ve done every single evening, 365 days a year, since 2 July 1928. At 8pm sharp, the road is closed and these lost men are remembered as The Last Post is played as a daily tribute to the fallen. Even during Covid one lone bugler, with no crowds, stood to sound the last post at 8pm every night. So far 32,877 ceremonies have taken place, and it gets me wondering what might be planned when they reach the same number of ceremonies as fallen men.

And the Menin gate was only a 5 minute walk from where we stayed at Christmas, so we went at 8pm on the first night we arrived, and then every night after that for five nights.

And you can hear the audio of the Last Post and our musings on the podcast episode (from 10mins).

When we visited Menin Gate in December 2022:

Boxing Day 2022 - The Last Post:

When Chris visited in May 2022:

Few more facts about Ypres for you:

It was one of the sites that hosted an unofficial Christmas Truce in 1914 between German and British Soldiers.

Adolf Hitler fought at Ypres during the First World War.

Its suffering didn’t end after the First World War. During World War II Belgium, and therefore Ypres, was occupied by Germany, who banned the Last Post ceremony from 1940-1944, so it was moved to Brookwood Military Cemetery in England temporarily - the largest Commonwealth war cemetery in the UK.

On the same evening that Polish forces liberated Ypres from the Germans, the ceremony resumed at the Menin Gate, in spite of heavy fighting still going on in other parts of the town.

After the Second World War Ypres was extensively rebuilt - not surprising for a town where it’s said that at its peak 20 shells were falling on the town every minute.

Ypres’ medieval and renaissance architecture was completely flattened during the war, it’s said someone on horseback could look across the whole town. But the whole of the town was reconstructed, much of it in the style of its original buildings during the 1920’s and 1930’s and it is now considered one of the best examples of post-conflict reconstruction, with most of its oldest looking buildings only being around 80 years old. I recommend Googling ‘rebuilding Ypres’ or 'Ypres before after war' to see images of the devastation and reconstruction.

It now has the title ‘city of peace’ and maintains a close friendship with Hiroshima, both witnessing warfare at its worst. Ypres - one of the first places where chemical warfare was employed, Hiroshima - suffering the debut of nuclear warfare.

Then, less than two kilometres from Passchendaele, is Tyne Cot, the world’s largest cemetery for Commonwealth soldiers, where 12,000 men lie buried, and we visited there too.

Not only is this where many soldiers were buried but it’s also the home of the ‘Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing’ - a list which commemorates 34,887 men from the UK and New Zealand Forces who died after 16 August 2017 (deaths before are named on the Menin Gate) - and this list is etched around the curved walls of the cemetery.

On arrival at Tyne Cot we parked the car and walked along a pathway towards the small, flat building that is the visitor centre. The cemetery is located in the area known as the Ypres Salient where Commonwealth, French, Belgian and German forces fought almost continuously throughout the First World War. So you’re surrounded by beautiful countryside, fairly flat, so you can see quite a long way, which gives you a poignant sense of realising that what you’re looking at is, or was, battlefields. As you near the visitor centre you can’t see the cemetery at all, it’s hidden at this point but you do start to hear something being played on a hidden speaker…

Every few seconds a name is read, from the ‘Memorial to the Missing’ register. You quickly get a sense of the enormity of these lists of men when you think how long you’d have to stand there to hear all the names. I did a quick bit of maths and if it takes 2 seconds to read each name, you’d be there for over 18 hours.

When you enter the Visitor Centre you have a similar speaker that continues the names, there’s no getting away from the loss of human life here.

The simple, but very modern room has many historical items, quotes, lists and information on the walls, and you soon notice that with the names being read out loud there are also photos of those lost coming up on a screen one by one, and a collage of them all together too.

A sign reads:

“During the First World War, the British Army decided not to repatriate the bodies of the soldiers to their country of origin, it was argued that those that fought together should remain united in death, close to the place where they died. Some were buried in makeshift battlefield cemeteries. Others remained where they fell. Many were lost in the mud of Passchendaele. Special army units searched the battlefields for bodies. Together with remains already buried in smaller cemeteries, they were taken to large ‘concentration’ cemeteries like Tyne Cot Cemetery.”

And on the walls are large quotes like:

‘The thought that Jock died for his country is no comfort to me. His memory is all I have left to love.’

John Low’s Fiancee, 10 January 1918

A very old, tatty letter taped together, dated 2 May, 1918 contains the words:

‘Dear Sir, In answer to your enquiry about your son - 707 Private. Matthew H. Austin, 35th Battalion, A.I.F. We deeply regret to inform you that we have received an unofficial report which we fear leaves little hope that he is alive. 1877 Private.A.Turner of the same unit, interviewed at the 3rd General Hospital, at Oxford stated that he saw your son lying dead on Oct 12th, 1917, at the Regimental Aid Post (an old pillbox) apparently killed by a machine gun bullet to the head. Another man remarked to Private.Turner “There is poor old Pies” (your son’s nickname)... We must point out that this report is strictly unofficial and your son is only as yet reported officially as Missing. We are making further enquiries, and will at once advise you of any information we may obtain. With our sincere sympathy in your anxiety which we full realise. Yours Faithfully, (Miss) Vera Deakin, Secretary.'

A form, filled out with gaps for names and dates reads:

‘Madam, It is my painful duty to inform you that no further news having been received relative to No. 242521, Rank Private, Regiment ⅕ York and Lancs who has been missing since 9.10.1917, the Army Council have been regretfully constrained to conclude that he is dead, and that his death took place on 9.10.1917 (or since).’

A visitor's book echoes the message ‘we will remember them’ over and over, and someone has quoted George Santayana: “Only the dead have seen the end of war.”

After you pass through this smallish building you then start a walk down a path on the outside of the northern boundary of the cemetery and it comes into view for the first time.

As you walk along the boundary you reach a road and turn left along the boundary wall to the cemetery's entrance, which is a stone archway containing more information, a timeline, a layout and images of the original wooden crosses that stood in their place before the final gravestones were laid. There is a note and old photo of Sergeant Lewis McGee who served with the Australian Infantry during the Third Battle of Ypres in 1917. His battalion captured the area where the cemetery is and Lewis singlehandedly stormed one of the nearby German bunkers. He was killed in action eight days later at 29 years old. For his courage he was awarded the Victoria Cross and is one of six recipients of it buried or commemorated at Tyne Cot. There’s also a metal safe that all the cemeteries have, which contains a book entitled ‘Cemetery Register with the Commonwealth War Graves Visitors’ Book’ and where you can find specific names and graves.

When you go through the archway you can either wander through the graves on either side or there’s a central path that leads up a slope to a big memorial at the end which includes - the Cross of Sacrifice (Great Cross), the War Stone and the Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing - which is a long curved wall containing all the names being read out loud at the visitor centre and this forms the eastern boundary wall - which also hides the cemetery from the car park behind it where you arrive. There are also three German blockhouses that were fought over during the war and they’re incorporated into the design of the cemetery.

I recorded some of my thoughts as I wandered around and you can hear those on the podcast episode.

(from 27:10 onwards)

Here's some images of where I was:

I think you’ll agree it’s not possible to encounter grief and loss like this and not be moved in some way. We so easily forget, as we look out of our window in countries not facing war now, that people have fought for this freedom we have. Young men in their teens, twenties, thirties, forties, ran towards certain death to keep our country from coming into the hands of others. So easily they could have thought it won’t make a difference, one life doesn’t matter, so easily they could have succumbed to the crippling fear they must have been carrying, the soul and mind-destroying grief that tore apart even those that survived. But they didn’t. They fought. Not because they were strong, but because they believed it was the right thing to do. Not all of them obviously, and many had no choice, but that doesn’t diminish their experience to me. And that is why I believe history is so important. Whether you agree with the war strategy, vehemently disagree, or look back with hindsight now and have some lofty opinion of it all, it happened, debate doesn’t change their death and if we don’t acknowledge it and remember it, then we can’t learn from it. We cannot cancel it out as our culture so often wants to do. And that is why we continue to hear the words ‘we will remember them’ because that’s the one thing we can do, we can make sure their lives weren’t given in vain, that’s the torch that has been passed to us, and as the first-hand experiences of fighting in our World Wars start to die out, it is down to us who heard the stories first hand to keep them alive, and make sure history never repeats itself in this way again.

In the spring of 1915, shortly after losing a friend in Ypres, a Canadian doctor, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae wrote his now famous poem after seeing poppies growing in battle-scarred fields. And it seems a fitting end to this episode.

In Flanders Fields In Flanders fields the poppies blow Between the crosses, row on row, That mark our place; and in the sky The larks, still bravely singing, fly Scarce heard amid the guns below. We are the Dead. Short days ago We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, Loved and were loved, and now we lie, In Flanders fields, Take up our quarrel with the foe: To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields. John McCrae

Comments